Abstract

Introduction

Michigan has implemented several of the tobacco control policies recommended by the World Health Organization MPOWER goals. We consider the effect of those policies and additional policies consistent with MPOWER goals on smoking prevalence and smoking-attributable deaths (SADs).

Methods

The SimSmoke tobacco control policy simulation model is used to examine the effect of past policies and a set of additional policies to meet the MPOWER goals. The model is adapted to Michigan using state population, smoking, and policy data starting in 1993. SADs are estimated using standard attribution methods. Upon validating the model, SimSmoke is used to distinguish the effect of policies implemented since 1993 against a counterfactual with policies kept at their 1993 levels. The model is then used to project the effect of implementing stronger policies beginning in 2014.

Results

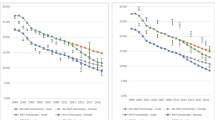

SimSmoke predicts smoking prevalence accurately between 1993 and 2010. Since 1993, a relative reduction in smoking rates of 22 % by 2013 and of 30 % by 2054 can be attributed to tobacco control policies. Of the 22 % reduction, 44 % is due to taxes, 28 % to smoke-free air laws, 26 % to cessation treatment policies, and 2 % to youth access. Moreover, 234,000 SADs are projected to be averted by 2054. With additional policies consistent with MPOWER goals, the model projects that, by 2054, smoking prevalence can be further reduced by 17 % with 80,000 deaths averted relative to the absence of those policies.

Conclusions

Michigan SimSmoke shows that tobacco control policies, including cigarette taxes, smoke-free air laws, and cessation treatment policies, have substantially reduced smoking and SADs. Higher taxes, strong mass media campaigns, and cessation treatment policies would further reduce smoking prevalence and SADs.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

World Health Organization (2009) History of the who framework convention on tobacco control. World Health Organization, Geneva

World Health Organization (2008) WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic, 2008. The MPOWER package, Geneva

Hopkins DP, Briss PA, Ricard CJ et al (2001) Reviews of evidence regarding interventions to reduce tobacco use and exposure to environmental tobacco smoke. Am J Prev Med 20:16–66

Levy DT, Gitchell JG, Chaloupka F (2004) The effects of tobacco control policies on smoking rates: a tobacco control scorecard. J Public Health Manag Pract 10:338–351

U.S. DHHS (2000) Reducing tobacco use: a report of the Surgeon General. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, Atlanta, GA

International Agency for Research on Cancer WHO (2009) Evaluating the effectiveness of smoke-free policies. IARC, Lyon

Chaloupka FJ, Straif K, Leon ME, Working Group International Agency for Resarch on Cancer (2011) Effectiveness of tax and price policies in tobacco control. Tob Control 20:235–238

Levy DT, Benjakul S, Ross H, Ritthiphakdee B (2008) The role of tobacco control policies in reducing smoking and deaths in a middle income nation: results from the Thailand SimSmoke simulation model. Tob Control 17:53–59

Currie LM, Blackman K, Clancy L, Levy DT (2013) The effect of tobacco control policies on smoking prevalence and smoking-attributable deaths in Ireland using the IrelandSS simulation model. Tob Control 22(e1):e25–32

Levy D, de Almeida LM, Szklo A (2012) The Brazil SimSmoke policy simulation model: the effect of strong tobacco control policies on smoking prevalence and smoking-attributable deaths in a middle income nation. PLoS Med 9:e1001336

Levy DT, Boyle RG, Abrams DB (2012) The role of public policies in reducing smoking: the Minnesota SimSmoke tobacco policy model. Am J Prev Med 43:S179–S186

Levy DT, Hyland A, Higbee C, Remer L, Compton C (2007) The role of public policies in reducing smoking prevalence in California: results from the California Tobacco Policy Simulation Model. Health Policy 82:153–166

Centers for Disease Control (1996) Cigarette smoking before and after an excise tax increase and an antismoking campaign-Massachusetts, 1990–1996. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 45:966–970

Biener L, Harris JE, Hamilton W (2000) Impact of the Massachusetts tobacco control programme: population based trend analysis. BMJ 321:351–354

Levy DT, Bauer J, Ross H, Powell L (2007) The role of public policies in reducing smoking prevalence and deaths caused by smoking in Arizona: results from the Arizona tobacco policy simulation model. J Public Health Manag Pract 13:59–67

Center for Disease Control and Prevention (2001) Tobacco use among adults: Arizona, 1996 and 1999. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 50:402–406

CDC State System. CDC website, 2015. Accessed 21 June 2015. http://nccd.cdc.gov/STATESystem/rdPage.aspx?rdReport=OSH_State.CustomReports&rdAgReset=True&rdShowModes=showResults&rdShowWait=true&rdPaging=Interactive

Levy DT, Chaloupka F, Gitchell J, Mendez D, Warner KE (2002) The use of simulation models for the surveillance, justification and understanding of tobacco control policies. Health Care Manag Sci 5:113–120

Levy D, Tworek C, Hahn E, Davis R (2008) The Kentucky SimSmoke tobacco policy simulation model: reaching healthy people 2010 goals through policy change. South Med J 101:503–507

Levy D, Rodriguez-Buno RL, Hu TW, Moran AE (2014) The potential effects of tobacco control in China: projections from the China SimSmoke simulation model. BMJ 348:g1134

Levy DT, Blackman K, Currie LM, Mons U (2013) Germany SimSmoke: the effect of tobacco control policies on future smoking prevalence and smoking-attributable deaths in Germany. Nicotine Tob Res 15:465–473

Levy DT, Bauer JE, Lee HR (2006) Simulation modeling and tobacco control: creating more robust public health policies. Am J Public Health 96:494–498

Levy DT, Nikolayev N, Mumford EA (2005) Recent trends in smoking and the role of public policies: results from the SimSmoke tobacco control policy simulation model. Addiction 10:1526–1537

National Center for Health Statistics (2011) Birth rates by age and gender. Access 15 Sept 2013. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/hdi.htm

National Center for Health Statistics (2010) Deaths by age and gender. Accessed 15 Sept 2013. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/hdi.htm

National Cancer Institute Sponsored Tobacco Use Supplement to the Current Population Survey (1992–1993). U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2001. Accessed 10 May 2015. http://www.census.gov/cps/methodology/techdocs.html

Hughes JR, Keely J, Naud S (2004) Shape of the relapse curve and long-term abstinence among untreated smokers. Addiction 99:29–38

U.S. DHHS (1990) The health benefits of smoking cessation: a report of the Surgeon General. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control, Office on Smoking and Health, Atlanta, GA

National Cancer Institute (1997) Cigarette smoking behavior in the United States. In: Burns D, Lee L, Shen L et al (eds) Changes in cigarette-related disease risks and their implication for prevention and control, smoking and tobacco control monograph 8. Bethesda, MD, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, pp 13–112

U.S. DHHS (1989) Reducing the health consequences of smoking: 25 years of progress: a report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health. Report No.: DHHS Publication No. [CDC] 89-8411

Orzechowski, Walker (2006) The tax burden on tobacco, historical compilation. Arlington, VA. Report No.: Volume 35

Consumer Price Index (2015). Accessed 5 June 2015. www.bls.gov

Levy DT, Friend K, Polishchuk E (2001) Effect of clean indoor air laws on smokers: the clean air module of the SimSmoke computer simulation model. Tob Control 10:345–351

Smoke-free air ordinance laws (2015) Accessed 8 Feb 2015. http://no-smoke.org/pdf/EffectivePopulationList.pdf

Quitline Stats (2015) Accessed 30 Aug 2015. http://www.naquitline.org/?page=800QUITNOWstats

Michigan Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (MiBRFSS) (2015) Accessed 10 May 2015. http://www.michigan.gov/mdhhs/0,5885,7-339-71550_5104_5279_39424—,00.html

Levy DT, Friend K (2002) Examining the effects of tobacco treatment policies on smoking rates and smoking related deaths using the SimSmoke computer simulation model. Tob Control 11:47–54

Jamal A, Agaku IT, O’Connor E, King BA, Kenemer JB, Neff L (2014) Current cigarette smoking among adults: United States, 2005–2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 63:1108–1112

Levy DT, Graham AL, Mabry PL, Abrams DB, Orleans CT (2010) Modeling the impact of smoking-cessation treatment policies on quit rates. Am J Prev Med 38:S364–S372

International Agency for Research on Cancer (2002) Monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans: tobacco smoke and involuntary smoking. International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon

Collaborators GBDRF, Forouzanfar MH, Alexander L et al (2015) Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks in 188 countries, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 386:2145–2191

Centers for Disease Control (2002) Annual smoking-attributable mortality, years of potential life lost, and economic costs: United States, 1995–1999. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 51:300–303

Levy DT, Ross H, Powell L, Bauer JE, Lee HR (2007) The role of public policies in reducing smoking prevalence and deaths caused by smoking in Arizona: results from the Arizona tobacco policy simulation model. J Public Health Manag Pract 13:59–67

Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act. 906(d)(1) U.S. 2009

Levy DT, Lindblom EN, Fleischer NL et al (2015) Public health effects of restricting retail tobacco product displays and ads. Tob Regul Sci 1:61–75

Levy DT, Blackman K, Currie LM, Levy J, Clancy L (2012) SimSmokeFinn: how far can tobacco control policies move Finland toward tobacco-free 2040 goals? Scand J Public Health 40:544–552

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2014) The health consequences of smoking—50 years of progress: a report of the Surgeon General. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, Atlanta, GA

Institute of Medicine (2015) Public health implications of raising the minimum age of legal access to tobacco products. National Academy of Sciences, Washington, DC

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge support from grant U01CA152956-03S2 by the National Cancer Institute of the US National Institute of Health. We thank Dr. Glenn Copeland from the Michigan Department of Community Health for helpful suggestions and facilitating access to relevant data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

None are declared.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Levy, D.T., Huang, AT., Havumaki, J.S. et al. The role of public policies in reducing smoking prevalence: results from the Michigan SimSmoke tobacco policy simulation model. Cancer Causes Control 27, 615–625 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-016-0735-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-016-0735-4